How Tech (and Business) Can Help Antarctica—And Our Future

Part 2 of 3: Antarctica Blog Series

A photo of Port Lockroy taken during Dr. Tiffany Vora’s voyage to Antarctica in November 2023.

In my previous post in this series, I shared part of a conversation with Dr. Mark Brandon, a polar oceanographer at the Open University, UK. As icebergs floated past us, I invited him to paint a picture of how climate change in Earth’s polar regions would impact our cities, our food systems, our supply chains, and our ways of life. If you haven’t read that post yet, I suggest checking it out!

After hearing Mark’s key insight for policymakers—that Antarctica is coming home to us through rising sea levels, weather changes, and more—I asked him the trillion-dollar question for futureproofing.

How would he uncover human impacts in the far South, and extract better insights into how changes in the polar regions are likely to affect us back home?

His top three wishes were for more polar satellite coverage, more powerful remote ocean surveying, and increased use of uncrewed aerial vehicles. Read on to find out why! Portions of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity.

You can’t manage what you can’t measure

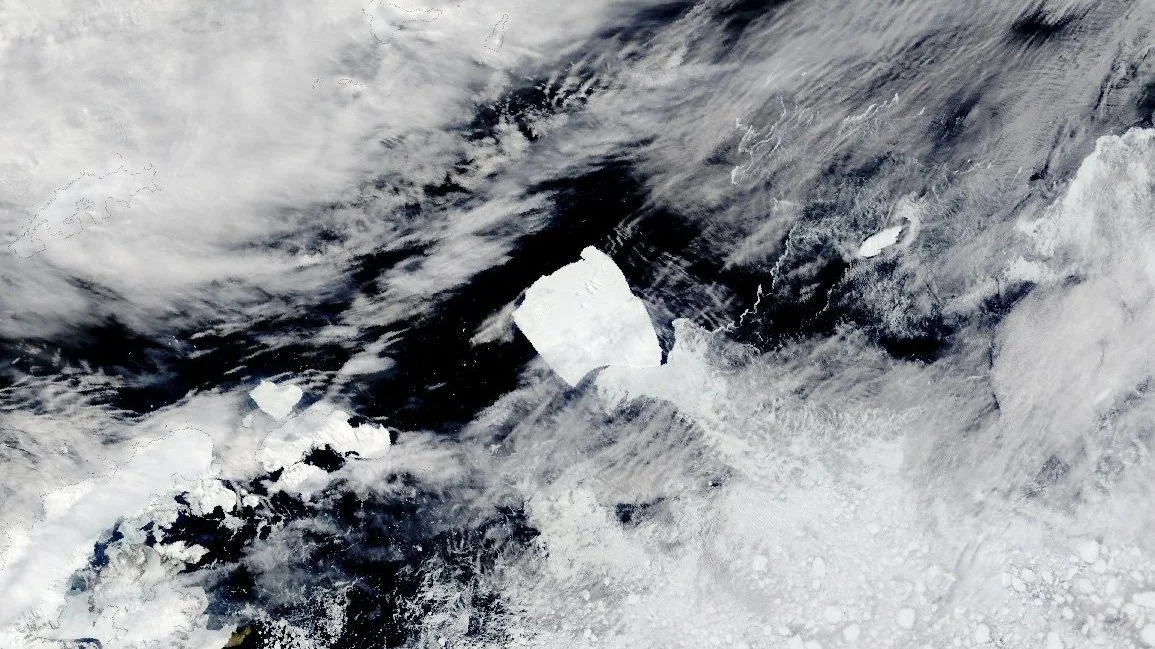

An image of the A-23 iceberg taken on November 28, 2023. The iceberg drifted near several islands at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, about 1,700 kilometers from its birthplace. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

Tiffany: If I handed you a magic wand and a blank check, what kind of technologies would be most useful to deploy down here [in Antarctica]? These could be technologies that exist elsewhere, and you don't have them yet, or ones that you can just make up out of whole cloth and tell me what your dream is.

Dr. Mark Brandon: First one is better satellites. Satellite orbits at the poles are difficult, because they take more fuel than around the equator and more temperate latitudes, so not many things go over the poles. So satellite records and radar satellites to measure the thickness [of polar ice and how it’s changing].

When we see stories in the media, it's very sexy to see a story with something really obvious like A23, an iceberg bigger than the size of Hawaii (see photo). Measuring things like icebergs the size of Hawaii is easy. Smaller icebergs are harder, but that's a tractable problem. It really is.

Remote ocean surveying for real-time insights

Dr. Mark Brandon: [Second is] remote ocean surveying. We have a system called Argo. [The devices are] basically steel tubes. You throw them in the water, they sink down to whatever depth you set (500 or 600 meters), and they drift along with the ocean currents, making measurements of temperature, salinity. Then at the programmed time you've set, they will pop back up to the surface and send the data back.

We've got probably about 2000 of those Argo devices around the world, in the Atlantic and the Pacific and Indian Oceans. We don't have many in the polar regions. They work in the polar regions. But one of the problems is, if they come up under ice, they can't transmit the data. So if a device could store the data, that would enable remote technologies in the ocean.

In the UK, we've pioneered autonomous underwater vehicles. Those sorts of technologies would be absolutely amazing to measure these ocean currents coming into Antarctica [and how they’re changing].

Unmanned aerial vehicles for bigger data

Dr. Mark Brandon: And the last one would be unmanned aerial vehicles, UAVs. The British and the Americans and the Europeans now have come up with remarkably good, high endurance, unmanned aerial vehicles for intelligence purposes.

There was a paper published two days ago, while we've been here, which has shown that a glacier about 150 miles south of where we've been [Cadman Glacier], in six years has had the most incredible change. And the only reason they know that is because they've had that sort of data.

If you were to fly a UAV across Antarctica once a month, through the summer months, for a few years, that would be striking.

Electromagnetic radiation doesn't pass through the ocean. It’s the same problem with ice. But with the right frequency of radio echo sounding, you fly your plane over the ice, fire off a radio echo sounding signal, and then it passes through the ice and you get a reflection of that. That's how we know most of the mountain ranges beneath the ice.

View from the Twin Otter, taken by Tiffany during a voyage to the Arctic in 2005.

To do that, we use Twin Otters, planes from the 1950s, that we still operate because they're incredibly robust. But that involves pilots flying gridlines, and there are areas of Antarctica that we don't really survey very well, but could be very important for future sea level rise. UAVs would enable us to close that gap, particularly if they were solar powered, so there wouldn't be a fuel problem.

Fundamentally the problem with climate change in Antarctica is that you've got two huge numbers. You've got snow that falls on Antarctica. That's a very big number, because Antarctica is very big. And then you've got ice that comes off Antarctica in the form of icebergs and melt. That's also a very big number. So you have a very big number and you take away a very big number.

That difference is what we're talking about. And so knowing those big numbers in the first place is the really important thing, so that we can be more certain about the difference.

Turning to experts across fields

Dr. Mark Brandon: My last point that I should say is, I'm a polar oceanographer. My expertise is on the marine life science ecosystem around Antarctica and how the ocean is melting sea ice and Antarctica. Your questions, of course, are incredibly broad and wide ranging, and jump across 10 different fields. I bow to all of my colleagues in those areas. I have opinions through working here for 30 years. But I'm not an expert [in all these fields].

Tiffany: Where could I go to find some of those experts?

Dr. Mark Brandon: There's a wonderful NGO called the Pew Foundation. And CCAMLR, which looks at Antarctic fisheries. The Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, ASOC, is a collection of NGOs concerned with the Southern Ocean. Both Pew and ASOC have expert scientific input that's relevant. For deep sea mining, that's kind of separate from the Antarctic issue, but there’s the American Geophysical Union, the European Geosciences Union.

What can we do today?

Dr. Tiffany Vora during her 2023 voyage to Antarctica with Homeward Bound. Image credits: Heidi Victoria

Despite his modest statement that he’s “not an expert”, Mark’s wishlist for polar science innovation brings up an incredibly important point. Note that he hasn’t asked for anything that isn’t achievable, in the short term, with the help of attention, funding, and determination. No sci-fi revolutions necessary!

My conversation with Mark points to some critical ways that all of us can help contribute to revealing more about our changing planet:

Satellites, drones, AI, and other exponential technologies can be found in innovation toolboxes across industries. How can we expand the use of tools that we already have in order to understand how our planet is changing?

Businesses generate enormous and diverse datasets from all over the world. Is your business already taking measurements that could be repurposed for climate investigations and insights into the future?

Governments remain an important source of funding for the basic scientific studies that Mark has highlighted here. Are you voting for a thriving, resilient future?

Remember VUCA? Well, a changing planet can change in unpredictable ways (see the story about the Cadman Glacier that Dr. Brandon pointed to). This wishlist of applying convergent technologies is meant to help all of us—as individuals, businesses, and communities—navigate a future that will be very different from anything in our recent past.

Stay tuned for the final post in this series, when I share Dr. Mark Brandon’s vision for the future—not just of Antarctica, but of our world. Is he optimistic?

About Tiffany

Dr. Tiffany Vora speaks, writes, and advises on how to harness technology to build the best possible future(s). She is an expert in biotech, health, & innovation.

For a full list of topics and collaboration opportunities, visit Tiffany’s Work Together webpage.

Get bio-inspiration and future-focused insights straight to your inbox by subscribing to her newsletter, Be Voracious. And be sure to follow Tiffany on LinkedIn, Instagram, Youtube, and X for conversations on building a better future.

Photos from Tiffany’s Antarctic Voyage

Donate = Impact

After a 19-day voyage to Antarctica aboard The Island Sky in November 2023, Tiffany has many remarkable stories to share & a wealth of insights to catalyze a sustainable future.

You can support her ongoing journey by making a contribution through her donation page. Your support will spread positive impact around the world, empower Tiffany to protect time for impact-focused projects, and support logistical costs for pro bono events with students & nonprofits.